I have just returned from a walk, and it is safe to say that today feels like the first day of winter – the coldest day of the year so far (it’s –1°C as I write). Passing the houses in my neighbourhood, I could already see Christmas beginning to take hold, with outdoor lights glowing and decorated trees twinkling in windows. I returned to a wave of heat when I opened the front door which made me think of warmth in the past – lighting fires, having a cosy bowl of soup. It seemed the perfect time to talk about the origins of cooking. So, grab a cocoa and a duvet, and read on.

Fire

Fire is one of humanity’s earliest technologies – a tool we learned to control, manipulate, and use to transform our environment, food, and daily lives. The control of fire was one of the most important turning points in human evolution, reshaping not only how our ancestors ate, but how they lived, learned, and related to one another. Controlling fire provided warmth in cold climates, protection from predators, and light that extended the day beyond sunset, allowing more time for social interaction and shared work. Crucially, fire made cooking possible, transforming tough or unsafe foods into soft, digestible, energy-rich meals that fuelled larger brains and healthier bodies. It also created a natural gathering place: the hearth became a centre of storytelling, learning, cooperation, and early culture. In many ways, fire did not simply help humans survive – it helped shape what it means to be human.

Fire remains essential today, even in different forms. From the heat of ovens and stoves to electricity – much of which is generated through combustion – fire underpins modern life. It enables industry, fuels transport, supports agriculture, and continues to bring people together around warmth and shared meals. Though managed more safely now, fire still carries cultural, emotional, and symbolic weight: a candle lit for remembrance, a fireplace in the home, a campfire around which stories are still told.

When Did Cooking Begin?

When did humans first start to cook? It is a fascinating and debated question in archaeology. Cooking transformed our ancestors’ relationship with food, fire, and each other, but finding clear proof is complex. Archaeological evidence of early cooking is very sparse and fragmentary. Fire use leaves limited traces, and food itself rarely survives over tens or hundreds of thousands of years. Most evidence comes from:

- Charred animal bones or plant remains

- Burnt soil or hearths

- Clues from the fossil record that show how our bodies changed over time

- Chemical residues in pottery (much later in the record – about 20,000 BP1 in Xianrendong Cave, Jiangxi, China)

Even where fire is found, it’s often hard to prove it was used for cooking rather than warmth or protection. That’s why claims about cooking more than a million years ago are debated – the record is incomplete and indirect. However, science is provisional: all hypotheses must be supported by evidence and justifiably accepted as true until further data suggests otherwise.

The most widely accepted evidence for the earliest cooking site comes from the oldest known cave occupation site in the world, Wonderwerk Cave in South Africa, where burnt animal bone and light plant ash were found alongside Acheulean hand-axes2 – tools made by Homo erectus. Studies show these materials were burned inside the cave rather than brought in by wildfires, suggesting early humans there may have used fire for cooking around one million years ago.

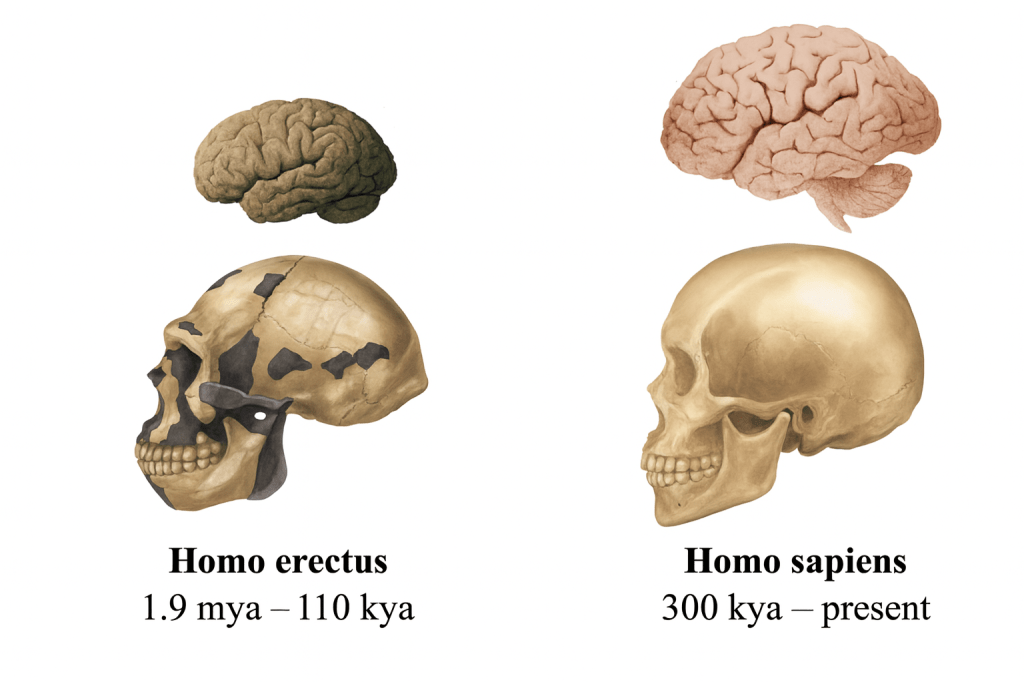

Some, like Richard Wrangham, believe that cooking began earlier. He argues that cooking began between 1.9 and 1.6 million years ago, allowing ancestors to gain more energy from food, grow bigger brains, and develop smaller teeth and jaws. Cooked food is softer and easier to digest, meaning less energy is spent eating and more can fuel the body and brain. The anatomical changes reflect cooking’s impact. Over time, teeth and jaws shrank, while brain size increased dramatically. Early Homo had brains similar in size to chimpanzees’, but after Homo erectus appeared about 1.9 million years ago, brain size tripled. Cooking also allowed smaller stomachs and intestines, freeing energy for a larger brain – the “expensive tissue hypothesis.”

Cooking may have shaped child-rearing too. A reliable, energy-rich diet allowed mothers to have children more often and care for them longer, promoting stronger family and social structures and greater survival.

Some suggest that cooking only became widespread less than half a million years ago, perhaps with Homo sapiens. Other sites with strong evidence for early cooking:

- Gesher Benot Ya’aqov, Israel – c. 780,000 years ago (evidence of the cooking of fish, burned seeds, wood, and stone tools; multiple repeated burning events, suggesting habitual fire use)

- Qesem Cave, Israel – c. 400,000 years ago (evidence of repeated use of a central hearth; clear signs of cooking such as roasted bones)

- Beeches Pit, Suffolk, England – c. 400,000 years ago (evidence of constructed hearths and repeated fires; associated with Homo heidelbergensis)

- Schöningen, Germany – c. 300,000 years ago (evidence of charred wooden spears and fire residues)

Earliest Evidence for Cooking in Ireland and in County Kildare

The earliest evidence for cooking in Ireland is dated to the Mesolithic period, in Mount Sandel, County Derry, with radiocarbon dating for activity on the site dating to 7,900-7,500 BC. Archaeologists found hearths, charred animal bones, and plant remains indicating controlled use of fire for cooking. As you will have seen above, England was populated much earlier than Ireland due to mass ice sheets covering Ireland during the Last Glacial Maximum4.

In County Kildare, the earliest evidence of cooking (that I can find so far) comes from a site on Rathbride Road in Kildare Town. Archaeologists uncovered darkened, crusty deposits inside fragments of an Early Neolithic carinated bowl, a pottery type dated to 3900–3600 BC. These blackened residues, known as accretions, form when a pot is repeatedly exposed to heat and food, making them a reliable sign that the vessel was used for cooking or heating food. They also found a saddle quern for grinding grain suggesting processing food as well as cooking; and later in date, two fulachtaí fia5 (burnt mounds) – Bronze Age troughs with heat-shattered stones, that may have been used to boil water for cooking.

The Enduring Power of Fire

The mastery of fire that began hundreds of thousands of years ago continues to shape our daily lives, connecting us to early humans. Even today, with most houses not having a burning fire, it still draws us in – last Christmas, the most-watched item on Netflix was an hour-long piece of footage of a crackling Birchwood fire, showing that the glow of the hearth still speaks to something ancient in us.

Whenever it began, controlling fire was a huge step forward, providing warmth, protection, light, and a social centre for early communities. Around the fire, humans shared food and knowledge, creating bonds and a sense of belonging – foundations for human culture.

The story of cooking is, in many ways, the story of what makes us human. Evidence from Wonderwerk Cave shows that even a million years ago, humans harnessed fire – not just as a survival tool, but as a source of nourishment, comfort, and community. We are, quite literally, a species shaped by cooking. Our bodies, brains, and societies evolved around the hearth. The first fires lit more than just food – they illuminated the way to what we would become.

- BP: Before Present with present fixed at AD 1950 ↩︎

- Acheulean tools, made primarily by Homo erectus and later Homo heidelbergensis (c. 1.7 million–200,000 years ago), included hand-axes, cleavers, flake tools, and choppers. Hand-axes are the most iconic, characterised by a bifacial, symmetrical shape. They were multi-purpose tools, likely used for butchering animals, chopping wood or plants, digging, scraping hides, and possibly even as weapons. ↩︎

- This is an AI-created image to show brain size difference and not a scientific representation. ↩︎

- Earth is still technically in an ice age (the 5th in the history of the Earth) – the Quaternary Ice Age, which began about 2.6 million years ago. But we are currently in an interglacial period called the Holocene, which started around 11,700 years ago after the Last Glacial Maximum (the peak of the Ice Age). During interglacials, most of the world’s land is ice-free, though large ice sheets remain in Greenland and Antarctica. These interglacial periods are warm phases that alternate with much colder glacial periods, which is why, despite our current relatively mild climate, the planet is still considered to be in an ice age.

The ice sheets in Ireland began melting at the end of the Last Glacial Maximum, around 19,000–18,000 years ago, but the process was gradual and it wasn’t until about 12,000 years ago that Ireland’s landscape was completely free of ice. The melting of the ice sheets created the lakes, rivers, and fertile soils of Ireland, shaping the island that humans began to inhabit.

Our earliest evidence for human activity in Ireland is inferred from the presence of a bear bone with butchery marks found in the Alice & Gwendoline Cave in County Clare, dated to c. 12,875 years ago. ↩︎ - Fulacht fiadh (singular): a type of Bronze Age cooking site found in Ireland, Britain, northern Europe, and parts of Scandinavia. They typically consist of a pit or trough filled with water, often surrounded by a horseshoe-shaped mound of burnt stones. Stones were heated in a fire and then placed in the water to boil it for cooking meat or other food.

The name comes from the Irish, fulacht (pit or cooking place) and fiadh (wild or referring to deer). To my knowledge, their name in Irish is the only language that refers to the trough and not the mound. I will have to investigate further. ↩︎

Leave a comment